Manga Written in Kanji

Manga Written in Kanji

WHAT IS MANGA AND WHERE DID IT COME FROM?

Over time, many people have asked this same question. Yet, many are not interested enough to do anything to find the answer. But, you are. So, as a means of quenching your curiosity, we provide you with a brief explanation of manga, as well as a detailed look into the history of manga. We have found that it is best to define and view manga within the entire scope of its rich history. However, we will start with the simple definition of manga as "Japanese comics," knowing that manga is so much more (Sanders). In this one word, the "synthesis [of] a long Japanese tradition of art that entertains" is defined (Schodt 21). While manga has not always been known by this name, it's existence has left an indelible mark on the past while forging a path into the future.

The earliest influences of Manga date back to ancient Japan. In the eighth century, CE, Horyuji Buddhist Temple was completely rebuilt after burning to the ground (Ito 458). When repairs were done on the temple in 1935, drawings resembling caricature figures and, according to Frederik Schodt in Manga! Manga! The World of Japanese Comics, "grossly exaggerated phalli" were discovered on wood boards taken down from the temple's ceilings (qtd. in Ito). These drawings are some of the earliest known Japanese comic art (Ito 458).

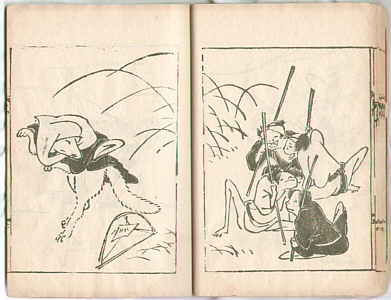

A scene from the Toba Sojo Scrolls

A scene from the Toba Sojo Scrolls

During the eleventh century, CE, a priest named Toba Sojo painted what is now referred to as "the Animal Scrolls" (Ito 458). These scrolls, or "choju giga," feature rabbits, monkeys and other animals "in silly activities, including farting contests" (Aoki). This satirical look at the lives of Buddhist monks is also an early example of drawings depicting events in sequential order. When unrolled the scrolls present the images in order from right to left, a reading technique that is still employed in reading manga today (Aoki). The Toba Sojo Scrolls are currently available in their entirety for viewing online.

While this type of parody and satire may seem irreverent to some, the Japanese found (and still find) great humor in Toba's scrolls. In the West, the Japanese are often stereotyped as being "serious, reserved, diligent" or "calculating, oversexed, [and] cunning" (Ito 456-7). However, according to Kinko Ito, the people of Japan "are humorous, witty and funny...once they bring down the formal fa├ƒ┬žade that they project to others, especially foreigners" (457). Toba's scrolls show that this love of satire and parody have a long-standing place in the history of Japan.

An 18th Century Otsu-e

1603-1867: Satire marked an evolution in manga. Yet, manga was about to evolve yet again. During the Tokugawa, period the town of Otsu, near Kyoto, sold Otsu-e, or "Otsu pictures," to commoners and people who were traveling on the main road from Kyoto to the north (Ito 458). Otsu-e began as a simple story with an inspiration of Buddhist folk art (MacWilliams 27). These manga focused on the specific theme of prayer, as Buddha was a strong central figure in the culture at the time. Tokugawa government was actively persecuting Christians and this influenced artists to draw manga filled with satire that was sacred as well as secular (and sometimes scandalous, which appealed to many of its purchasers).

Tobae began to be drawn during the Hoei period (1704-1711) and marks the "start of the commercialization of manga" as they were among the first images printed using a new woodblock printing technique and sold throughout Japan (Ito 459). During the Hoei period, Japan experienced a boom in urbanization and "publising businesses were flourishing" (Ito 459). These pictures were especially popular as they depicted everyday Japanese life in funny and satirical ways.

An early example of satirical Tobae

During the Genroku (1688-1704) and Kyoho (1716-1736) periods, picture books known as Akahon became very popular (Ito 459). Akahon literally means "red book" (MacWilliams 29). These picture books were commonly referred to by the color of their cover. They focused on folk and fairy tales such as The Peach Boy, The Battles of the Monkey and the Crabs and Click-Clack Mountain (Ito 459). Over time, the audience for Akahon changed from children to adults, while remaining in picture-only form.

In 1765, Harunobu Suzuki started multicolor woodblock printing, marking the beginning of the golden age of ukiyo-e ("the pictures of the floating world") color prints (Ito 459). When ukiyo-e moved from depicting the hedonistic amusements of the merchant caste to "the woodblock-printing version" of art, it thrived (Ito 459).

Katsushika Hukusai was well-known for sketches and dynamic compositions in the ukiyo-e style. Hokusai's msterpieces are know as The 36 Views of Mt. Fuji which illustrate novels, and other paintings/drawings of beauties and samurais (MacWilliams 29). Hakusai is also famously known for coining the word "manga," as it became associated with his work Hokusai Manga, in which her drew caricatures that was critical of the government, "aristocratic and samurai class[es]" (Ito 460). These renderings immediately made his works best-sellers (Ito 460).

1868-1912: The Meiji Era was a time period in which Japan ended the Shogun feudal system and brought back imperial rule. While the majority of popular manga in the 18th century satirized Japanese political figures, it wasn't until 1853, when Commodore Perry, a U.S. naval officer, introduced Japan to the western world that manga would eveolve yet again (Aoki).

"Prior to [...] 1868, Japanese artists usually drew themselves with small eyes and mouths and variable proportions [...]" but as new western ideas began to infiltrate Japanese traditional values, manga and its artists were influenced and inspired by imported artistic styles such as French and English political cartoons (Schodt 60). These styles, found in magazine like The Japan Punch, soon had artists blending western comics with Japanese ideas (Aoki).

During the Genroku (1688-1704) and Kyoho (1716-1736) periods, picture books known as Akahon became very popular (Ito 459). Akahon literally means "red book" (MacWilliams 29). These picture books were commonly referred to by the color of their cover. They focused on folk and fairy tales such as The Peach Boy, The Battles of the Monkey and the Crabs and Click-Clack Mountain (Ito 459). Over time, the audience for Akahon changed from children to adults, while remaining in picture-only form.

In 1765, Harunobu Suzuki started multicolor woodblock printing, marking the beginning of the golden age of ukiyo-e ("the pictures of the floating world") color prints (Ito 459). When ukiyo-e moved from depicting the hedonistic amusements of the merchant caste to "the woodblock-printing version" of art, it thrived (Ito 459).

Katsushika Hukusai was well-known for sketches and dynamic compositions in the ukiyo-e style. Hokusai's msterpieces are know as The 36 Views of Mt. Fuji which illustrate novels, and other paintings/drawings of beauties and samurais (MacWilliams 29). Hakusai is also famously known for coining the word "manga," as it became associated with his work Hokusai Manga, in which her drew caricatures that was critical of the government, "aristocratic and samurai class[es]" (Ito 460). These renderings immediately made his works best-sellers (Ito 460).

1868-1912: The Meiji Era was a time period in which Japan ended the Shogun feudal system and brought back imperial rule. While the majority of popular manga in the 18th century satirized Japanese political figures, it wasn't until 1853, when Commodore Perry, a U.S. naval officer, introduced Japan to the western world that manga would eveolve yet again (Aoki).

"Prior to [...] 1868, Japanese artists usually drew themselves with small eyes and mouths and variable proportions [...]" but as new western ideas began to infiltrate Japanese traditional values, manga and its artists were influenced and inspired by imported artistic styles such as French and English political cartoons (Schodt 60). These styles, found in magazine like The Japan Punch, soon had artists blending western comics with Japanese ideas (Aoki).

"At the dawn of the 20th century, manga reflected the rapid changes in Japanese society [...]" (Aoki). Influential artists that contributed to the development of modern manga include: Rakuten Kitazawa (1876-1955), who "[...] founded Tokyo Puck, a magazine showcasing Japanese cartoonists;" and Ippei Okamoto (1886-1948), "[...] the founder of Nippon Mangakai, the first Japanese cartoonists society" (Aoki).

1912- Present: As Manga became more popular, so did the number of artists who drew manga. These artists, known as mangaka, soon faced a challenge that was unlike any they had ever encountered when World War I started in 1914. In 1915 the “Shonen Club” was established as a magazine for young children to read (Aoki). World War I ended in 1919; however it left an impression on the cartoonists who then sought to teach the youth about the patriots’ sacrifice for their country. Miyazaki Ichiu created stories in 1922 through the Shounene Club. His stories depicted “Japanese valour and the Yamato spirit” (Griffiths). During 1923, Shojo Club mangazine was founded to appeal to the feminine populous. Eventurally manga was used for propaganda in World War II.

"At the dawn of the 20th century, manga reflected the rapid changes in Japanese society [...]" (Aoki). Influential artists that contributed to the development of modern manga include: Rakuten Kitazawa (1876-1955), who "[...] founded Tokyo Puck, a magazine showcasing Japanese cartoonists;" and Ippei Okamoto (1886-1948), "[...] the founder of Nippon Mangakai, the first Japanese cartoonists society" (Aoki).

1912- Present: As Manga became more popular, so did the number of artists who drew manga. These artists, known as mangaka, soon faced a challenge that was unlike any they had ever encountered when World War I started in 1914. In 1915 the “Shonen Club” was established as a magazine for young children to read (Aoki). World War I ended in 1919; however it left an impression on the cartoonists who then sought to teach the youth about the patriots’ sacrifice for their country. Miyazaki Ichiu created stories in 1922 through the Shounene Club. His stories depicted “Japanese valour and the Yamato spirit” (Griffiths). During 1923, Shojo Club mangazine was founded to appeal to the feminine populous. Eventurally manga was used for propaganda in World War II.

In 1931, Henry Yoshitaka Kiyama’s book “The Four Immigrants Manga” was published in Japan, before being published in the United States as one of the first modern comic books styles seen in the United States. Also in 1931, the publishing company Kodansha published Tagawa Suiho’s Norakuro, about a black dog that takes up arms to fight. This story's purpose was to teach the children of Japan the value of sacrificing oneself for Japan, and to learn the importance of valor on the battlefield. "Ganbatte," which means “do your best,” was typically the phrase children cried out after reading Norakuro (Aoki). Shin Nippon Mangaka Kyokai was a government supported trade organization that all mangakas had to join (Aoki). This was the start of using mangakas for propaganda purposes in 1937.

In 1946 Osamu Tezuka’s first work to be serialized as a professional, Diary of Ma-Chan, was published. It is about Ma-chan and his friend Ton-Chan and their life in post-WWII Japan. During the same year, Hasegawa Machiko emerged as one of the pioneering female manga artists of her time. She authored Sazae-san, which was serialized in Asashi newspaper. It was about family life from a housewife’s perspective. Akabon or “red books” first appeared in 1947 and were known for their extensive use of red ink to add tone and depth to the images, as well as being bound in red covers (Aoki). These books were cheap and it gave many struggling mangakas their big break. Yet, while Akabon were serialized stories, the publication of Shin Takarijima by Osamu Tezuka marked the first time an entire manga story was published as a book (Phillipps 69).

After World War II ended, there were numerous manga magazines created: Manga kurabu (manga club), VAN, Kodomo manga shim bun (Children's Manga Newspaper), Kumanbati (The Hornet), Manga shonen (Manga Boys), Tokyo Pakku (Tokyo Puck), and Kodomo Manga kurabu (Children's Manga club) (MacWilliams 35). However, the boom of these specific manga was short-lived -- only three years. The main factor for this short boom was because of the suffering many Japanese experienced after war. Even though the manga produced reflected the poverty and famine most Japanese were experiencing, these magazines still declined in popularity.

In 1931, Henry Yoshitaka Kiyama’s book “The Four Immigrants Manga” was published in Japan, before being published in the United States as one of the first modern comic books styles seen in the United States. Also in 1931, the publishing company Kodansha published Tagawa Suiho’s Norakuro, about a black dog that takes up arms to fight. This story's purpose was to teach the children of Japan the value of sacrificing oneself for Japan, and to learn the importance of valor on the battlefield. "Ganbatte," which means “do your best,” was typically the phrase children cried out after reading Norakuro (Aoki). Shin Nippon Mangaka Kyokai was a government supported trade organization that all mangakas had to join (Aoki). This was the start of using mangakas for propaganda purposes in 1937.

In 1946 Osamu Tezuka’s first work to be serialized as a professional, Diary of Ma-Chan, was published. It is about Ma-chan and his friend Ton-Chan and their life in post-WWII Japan. During the same year, Hasegawa Machiko emerged as one of the pioneering female manga artists of her time. She authored Sazae-san, which was serialized in Asashi newspaper. It was about family life from a housewife’s perspective. Akabon or “red books” first appeared in 1947 and were known for their extensive use of red ink to add tone and depth to the images, as well as being bound in red covers (Aoki). These books were cheap and it gave many struggling mangakas their big break. Yet, while Akabon were serialized stories, the publication of Shin Takarijima by Osamu Tezuka marked the first time an entire manga story was published as a book (Phillipps 69).

After World War II ended, there were numerous manga magazines created: Manga kurabu (manga club), VAN, Kodomo manga shim bun (Children's Manga Newspaper), Kumanbati (The Hornet), Manga shonen (Manga Boys), Tokyo Pakku (Tokyo Puck), and Kodomo Manga kurabu (Children's Manga club) (MacWilliams 35). However, the boom of these specific manga was short-lived -- only three years. The main factor for this short boom was because of the suffering many Japanese experienced after war. Even though the manga produced reflected the poverty and famine most Japanese were experiencing, these magazines still declined in popularity.

Due to the aftereffects of the war, it was not until the 1950s that manga blossomed. Osamu Tezuka was a major driving force in the manga industry. He provided a solid foundation in which future mangakas could use as a reference in creating their own stories. He is known as the “God of Comics” (Schodt 63). In the 1950s, Tezuka created and released “Astro Boy” also known as “Mighty Atom” and countless other works. However, saome say his work did not come into full fruition until the 1960s with the publication of his work Jungle Taitei or Kimba the White Lion, the first of Tezuka's work to be animated in full color in 1965. Tezuka’s career in manga allowed him to expand the genres that were once so limited due to government interference. He showed all of Japan that manga does

not only portray childish stories, but that it can be a cultural goldmine for readers of all ages.

Due to the aftereffects of the war, it was not until the 1950s that manga blossomed. Osamu Tezuka was a major driving force in the manga industry. He provided a solid foundation in which future mangakas could use as a reference in creating their own stories. He is known as the “God of Comics” (Schodt 63). In the 1950s, Tezuka created and released “Astro Boy” also known as “Mighty Atom” and countless other works. However, saome say his work did not come into full fruition until the 1960s with the publication of his work Jungle Taitei or Kimba the White Lion, the first of Tezuka's work to be animated in full color in 1965. Tezuka’s career in manga allowed him to expand the genres that were once so limited due to government interference. He showed all of Japan that manga does

not only portray childish stories, but that it can be a cultural goldmine for readers of all ages.

The 1970s was a time of change and a growth in passion for many manga readers. A new genre entered the world of manga during this decade. This specific genre, shojo manga, grabbed many young girls' attention. In this genre, cute heroines are beautifully drawn, making the pictures captivating to young girls. In 1972 many of the female artists who desired to become successful in the manga industry began drawing for the new female audiences reading shojo manga. Maki Miyako was the first to emphasize the "ladies comics" manga style in her manga (Masami).

During the early 1970's, manga was heavily focused on Japan's success, specifically in the area of sports. Mark MacWilliams gives an example of two such stories with Sainwa V and Attaku namba. Those two stories include "sportsmanship, friendship, injuries, fights, falling in love with a handsome male coach, competition, jealously, dogged efforts, and any other human emotions involved in winning games" (MacWilliams 40). These subjects provided a different view of the use of sports in showing readers how "to persevere in any situation and to always work hard in order to accomplish one's goals" (MacWilliams 40). This new moralistic idea influenced many women to become modern career people while also searching for love. One of women readers' favorite manga during this time was The Rose of Versailles. This manga series was created by Riyoko Ikeda, and is an epic story that deals with the French court in the years and days leading up to the French Revolution.

Men, specifically businessmen, read manga so mangaka began to draw within the themes of academic or educational stories. These stories created a new genre in manga known as "information manga" (Mac Williams 42). The 1970's also saw many other additions to the genres of manga. In 1973 Keiji Nakazawa's work Barefoot Gen began to be serialized. Barefoot Gen embodies what readers were looking for at the time; a rich story for an older generation. Barefoot Gen is a comic reflection of the realism of history.

The 1970s was a time of change and a growth in passion for many manga readers. A new genre entered the world of manga during this decade. This specific genre, shojo manga, grabbed many young girls' attention. In this genre, cute heroines are beautifully drawn, making the pictures captivating to young girls. In 1972 many of the female artists who desired to become successful in the manga industry began drawing for the new female audiences reading shojo manga. Maki Miyako was the first to emphasize the "ladies comics" manga style in her manga (Masami).

During the early 1970's, manga was heavily focused on Japan's success, specifically in the area of sports. Mark MacWilliams gives an example of two such stories with Sainwa V and Attaku namba. Those two stories include "sportsmanship, friendship, injuries, fights, falling in love with a handsome male coach, competition, jealously, dogged efforts, and any other human emotions involved in winning games" (MacWilliams 40). These subjects provided a different view of the use of sports in showing readers how "to persevere in any situation and to always work hard in order to accomplish one's goals" (MacWilliams 40). This new moralistic idea influenced many women to become modern career people while also searching for love. One of women readers' favorite manga during this time was The Rose of Versailles. This manga series was created by Riyoko Ikeda, and is an epic story that deals with the French court in the years and days leading up to the French Revolution.

Men, specifically businessmen, read manga so mangaka began to draw within the themes of academic or educational stories. These stories created a new genre in manga known as "information manga" (Mac Williams 42). The 1970's also saw many other additions to the genres of manga. In 1973 Keiji Nakazawa's work Barefoot Gen began to be serialized. Barefoot Gen embodies what readers were looking for at the time; a rich story for an older generation. Barefoot Gen is a comic reflection of the realism of history.

In the 1980s a new market trend started that became beneficial to many mangakas. “Comiket” or “Comike” is short for comic markets

In the 1980s a new market trend started that became beneficial to many mangakas. “Comiket” or “Comike” is short for comic markets  in which amateur artists sell their original works (Masami 28). This was an avenue that gave an opportunity to those who wanted to join the industry and be discovered by one of the well-known publishing companies. One famous group to come from Comike is the group called CLAMP which consists of four mangakas name Igarashi Satsuki, Ohkawa Ageha, Nekoi Tsubaki, and Mokona.

Akira by Katsuhiro began its serialization in the 80s. Akira was the first manga to be translated in its entirety into English. It was in this decade that many of the well known manga artists released some of their breakout works. For example Dr. Slump by Akira Toriyama who later created Dragon Ball and Dragon Ball Z. The manga Maison Ikkoku created by Rumiko Takahashi during this time lead to the artist’s work on Inuyasha.These manga artists were able to obtain successful careers through the rising publishing company "Shueisha Publishing" (Thorn). Their " Weekly Shonen Jump" magazine grew rapidly and has maintained the number one rank in circulation in Japan through today (Thorn). Countless titles from the 1980s soon became the catalyst to expanding the comic industry in the United States.

As the 1980s came to a close, the works of numerous mangakas continued serialization through the 1990s (some are still being serialized today). It was during the 1990s that the culmination of all the previous changes in manga come to full fruition. The countless hits that influenced the young careers of different artist was then exhibited in their own works. Even making small comedic puns made reference to older comics. For example, when you see a panel where the characters are doing a sentai pose or Power Rangers stance, it is a clear reference to Kamen Rider by Shotaro Ishinomori.

Though some mangakas still continue their serialization from the 1980s to now, (like Berserk by Kentaro Miura), as new talents enter the manga industry, the older mangakas often draw their stories to a close. Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms by Fumiyo Kouno is an excellent example of the culmination of many earlier influences and how manga will continue to evolve. Town of Evening Calm was first serialized in 2003, even though it has the look of a manga drawn in the 1950s. The story takes place 10 years after the atomic bomb fell on Hiroshima. Even though it is considered by many as a literary text, rather than popular, it made a large impact on the popular market. The artists' work that came before Fumiyo provided guidance for her to create an award-winning manga. Town of Evening Calm provides a example of how manga is ever-evolving, and that even though change is inevitable, there will always be remnants of the old comics as they serve as constant inspiration for the next generation.

in which amateur artists sell their original works (Masami 28). This was an avenue that gave an opportunity to those who wanted to join the industry and be discovered by one of the well-known publishing companies. One famous group to come from Comike is the group called CLAMP which consists of four mangakas name Igarashi Satsuki, Ohkawa Ageha, Nekoi Tsubaki, and Mokona.

Akira by Katsuhiro began its serialization in the 80s. Akira was the first manga to be translated in its entirety into English. It was in this decade that many of the well known manga artists released some of their breakout works. For example Dr. Slump by Akira Toriyama who later created Dragon Ball and Dragon Ball Z. The manga Maison Ikkoku created by Rumiko Takahashi during this time lead to the artist’s work on Inuyasha.These manga artists were able to obtain successful careers through the rising publishing company "Shueisha Publishing" (Thorn). Their " Weekly Shonen Jump" magazine grew rapidly and has maintained the number one rank in circulation in Japan through today (Thorn). Countless titles from the 1980s soon became the catalyst to expanding the comic industry in the United States.

As the 1980s came to a close, the works of numerous mangakas continued serialization through the 1990s (some are still being serialized today). It was during the 1990s that the culmination of all the previous changes in manga come to full fruition. The countless hits that influenced the young careers of different artist was then exhibited in their own works. Even making small comedic puns made reference to older comics. For example, when you see a panel where the characters are doing a sentai pose or Power Rangers stance, it is a clear reference to Kamen Rider by Shotaro Ishinomori.

Though some mangakas still continue their serialization from the 1980s to now, (like Berserk by Kentaro Miura), as new talents enter the manga industry, the older mangakas often draw their stories to a close. Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms by Fumiyo Kouno is an excellent example of the culmination of many earlier influences and how manga will continue to evolve. Town of Evening Calm was first serialized in 2003, even though it has the look of a manga drawn in the 1950s. The story takes place 10 years after the atomic bomb fell on Hiroshima. Even though it is considered by many as a literary text, rather than popular, it made a large impact on the popular market. The artists' work that came before Fumiyo provided guidance for her to create an award-winning manga. Town of Evening Calm provides a example of how manga is ever-evolving, and that even though change is inevitable, there will always be remnants of the old comics as they serve as constant inspiration for the next generation.

Works Cited

Aoki, Deb. "Early Origins of Japanese Comics." About.com. The New York Times Company. 2010. Web. 27 Feb. 2010. Gravett, Paul. Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics. New York: Harper Design International., 2004. Griffiths, Owen. "Militarizing Japan: Patriotism, Profit, and Children's Print Media, 1894-1925." JapanFocus. The Asian-Pacific Journal. 22 Sept. 2007. Web. 5 Mar. 2010. Japan Punch. Lot 17/Sale 5316. Christie's. 2009. Web. 8 Mar. 2010. Kinko, Ito. "A History of Manga in the Context of Japanese Culture and Society." Journal of Popular Culture V. 38 No. 3 (February 2005)P. 456-75, 38.3 (2005): 456-475. Print. MacWilliams, Mark W. "Manga in Japanese History." Japanese Visual Culture Explorations in the World of Manga and Anime (East Gate Book). Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 2008. 26-47. Print. Manga in Knaji. Manga. New World Encyclopedia. 8 Feb. 2009. Web. 8 Mar. 2010. Masami, Toku. "Shojo Manga! Girls' Comics! A Mirror of Girls' Dreams." Mechademia 2: Networks of Desire (2007): 19-32. Print. Otsu-e. Flickr. Yahoo. 4 July 2004. Web. 8 Mar. 2010. Phillipps, Susanne. "Characters, Themes, and Narrative Patterns in the Manga of Osamu Tezuka." Japanese Visual Culture: Explorations in the World of Manga and Anime. Ed. Mark MacWilliams. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 2008. 68-90. Print. Sanders, Joe. California State University, San Bernardino. English 315 Japanese Comics and Animation. 13 Jan. 2010. Lecture. Schodt, Frederik. Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga. Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press, 1996. Print. Thorn, Matt. "Manga-gaku." Matt Thorn. Matt Thorn. 2005. Web. 15 Mar. 2010. Tobae. EliteTurks. 2010. Web. 12 Mar. 2010. Toba Scrolls. Tezuka: The Marvel of Manga. AAMDocents. 1 June 2007. Web. 9 Mar. 2010.Ideas, requests, problems regarding CSUSB Community Wiki? Send feedback